Good coffee has finally arrived in Switzerland

The third wave is here! No, I'm not talking about the virus for once; today, it's all about coffee. Thanks to small roasteries and bold baristi, Switzerland has belatedly caught up with the current coffee scene.

«Two lattes with this month's roast, please,» requests one of the two young women at a small window at Zurich's Goldbrunnenplatz. She has brightly-coloured roots like Billie Eilish, while her companion is hiding under a big hood. They chat about boys, exam stress and the resulting depression. Just your average youngsters at Starbucks. Except that the window doesn't belong to the big American chain. It's the takeaway window of ViCafe (in German), which has taken Zurich and Basel by storm. ViCafe has ditched mochas and pumpkin spice in favour of coffees from a range of hand-picked sources. There are no sweet syrups; just milk and plant-based alternatives. «We know 90 per cent of our coffee farmers personally,» adds owner Ramon Schalch, who successfully kicked things off six years ago with the espresso bar at Goldbrunnenplatz. There are now six bars in Zurich, two in Basel and one in Eglisau. «The third wave has well and truly arrived in Switzerland. As usual, we're lagging a bit behind when it comes to trends,» says Schalch.

He's not talking about the pandemic; he means the third wave of coffee culture. It's a movement that views coffee as a luxury – on a par with wine – rather than just workplace doping. The origin of the coffee beans is transparent and the drinks are prepared according to the type of bean used. The third wave dispensed with sticky vanilla syrups and chocolate and cream combos long ago. Having taken hold in the US at the turn of the millennium, the trend has only really established itself in Switzerland in the last two or three years.

Three waves, three ideologies

First wave, around 1900: cheap coffee floods the market

At the end of the 19th century, coffee went from being a luxury to a mass product. Quality didn't come into it – coffee was just a vehicle for caffeine. Ground and packed into cans, litres of low-quality beans were drunk in the form of filter coffee. Coffee was a pick-me-up with no quality requirements.

During the first wave, it's said that the espresso machine was invented in Italy and the coffee world was revolutionised. Angelo Moriando was looking for a way to shorten the long brewing time of filter coffee. In 1884, he patented a machine that pushed water through the coffee grounds at low pressure. 22 years later, Desiderio Pavoni patented the «caffè espresso», a low-pressure, steam-powered machine. The result was burnt, bitter, watery coffee. And there was no cream in sight.

The first froth was made by Achille Gaggia's machine from 1938. This version was operated by hand, using water instead of steam and at a now-common pressure of 8 – 10 bar. While the Italians began to value this new kind of coffee, the rest of the world was still living in the caffeine stone age. Italy was too small for a coffee revolution – that took the US and an astute European.

Second wave, from 1966: it's up to a European to lead the charge

Alfred Peet was a Dutch immigrant who was so shocked by the muddy water-like coffee that he was served in the US in the '60s that he set up his own coffee bar on the spot. His father was a coffee trader in Amsterdam. Peet had been learning about quality his whole life. At least coffee houses and roasters in Europe had some kind of quality requirements – in the US, quantity and price were the key factors. When he opened «Peet’s Coffee Bar» in Berkeley, California, in 1966, he knew how the business worked:

Good quality was hard to come by in the US because the country didn’t trade in good coffee beans. It was as simple as that. They always tried to sell me the beans that everyone else had. That was exactly what I didn’t want. If I do what everyone else is doing, there's no point.

Peet began to roast beans himself. His intense, aromatic coffees became legendary – he soon sold not only drinks, but beans too. In 1971, Peet was the first supplier of green coffee for the start-up founded by friends Jerry Baldwin, Gordon Bowker and Zev Siegl. They named it after the chief mate in Herman Melville's novel «Moby-Dick»: Starbucks. The Seattle start-up opened one outlet after another, mostly close to popular smaller cafes. The strategy worked: Starbucks pushed the small coffee shops out of US city centres. Better quality coffee and individuality proved popular in the form of a range of sugary syrups.

The Swiss quirk of the café crème

While Peet and Starbucks were starting a coffee revolution in the US with the second wave, Switzerland was a no man's land. Filter coffee was still the standard – espresso was only an option on holiday in Italy. The automated coffee machine (in German) was invented by Arthur Schmed in 1985. It was said to herald the second wave in Switzerland, which came in the form of the «café crème». Stronger and more aromatic than filter coffee, but not as short or thick as Italian espresso. The «crème» is still widely known as the questionable gold standard of Swiss coffee culture. Although Italian restaurants and coffee shops have been serving espresso from proper portafilters since the '90s, more traditional restaruants that are usually called «Löwen», «Bären» and «Adler» are still faithful to the watery ditchwater from the automated machine. The price of a «café crème» has become a financial index (in German). This Swiss «Big Mac index», compares the average price between the German-speaking cantons, gives an indication of the wealth of Swiss citizens and turns coffee grounds into concrete figures. «Cafetier Suisse» (in German) reported that the average price of a «café crème» increased a full six per cent across the country between 2014 and 2019, from 3.97 to 4.21 Swiss francs. Meanwhile, the real earnings of Swiss residents only grew by around three and a half per cent over the same time period. Whether the average quality of the coffee rose by six per cent is unknown.

Coffee beats chocolate and cheese

Coffee isn't just important in the Swiss economy – it's important for the economy. Starbucks' coffee machines are made by Thermoplan in Weggis. Schaerer, Franke, Solis, Egro, Jura, Saeco, Cafina, HGZ… The list of Swiss coffee machine manufacturers is a long one, and their products are used around the world. And we haven't even mentioned the largest one yet: Nespresso. Three factories in French-speaking Switzerland produce the whole world's supply of its popular capsules. Nespresso is a big part of why Switzerland is now a big player in the coffee trade. The exports (in German) are more significant than that of chocolate or cheese – products that are usually associated with Switzerland abroad. If the automated machine marked the beginning of Switzerland's second wave, the capsules are the peak. From nail studios to carpenters' workshops and travel agents, capsule holders form the backbone of Swiss SMEs and the «powerful 19-bar pump» is their heartbeat.

Nespresso had a slow start. The system was invented and patented by Nestle employee Eric Favre in 1976. To start with, it was too expensive and complicated. Initial attempts to gain a foothold in Switzerland and Japan failed. The machines were too expensive and customers weren't yet ready for them. Nestle wanted to bury the project when Jean Paul Gaillard joined at the end of the 1980s. His solution was simple and ingenious: selling Nespresso machines more cheaply and allowing external manufacturers to assemble them. To counter this, Gaillard made the capsules more expensive. Because Nespresso closely guards the patent for the capsules, it cashes in with every cup of the resulting coffee.

Third wave, from 2000: fair and fancy

While the capsule frenzy was starting at the turn of the millennium, the third wave of coffee culture was getting off the ground in the US. Trish Rothgeb coined the term in a 2002 newsletter article for the Roasters Guild. In it, she details a trip to Oslo and how baristi there are breaking the rules. Lighter roasts for espresso, shorter extraction times and «single origin» beans from one specific plantation. Fairtrade sourcing is as big a part of the third wave as micro or small roasteries which only process small amounts.

Rothgeb now thinks the third wave of coffee culture is nearing its end, but it only reached Switzerland a few years ago. Just five years ago, I wrote a column in the Badener Tagblatt (in German) about how bad the coffees were in my hometown. Since then, a few brave souls like «Gap’s Cup» have dared to ride the third wave on the small-town scene. It's a sign that the coffee trend has reached beyond big cities like Zurich and Basel.

Zurich has already been competing on the international stage for some time. To name just three examples, Emi Fukahori from café MAME won a world title (in German) in 2018, Milo Kamil has run the Coffee Lab (in German) for ten years and teaches interested parties about coffee, and Miro has mixed up the region with its roasts and coffee trucks.

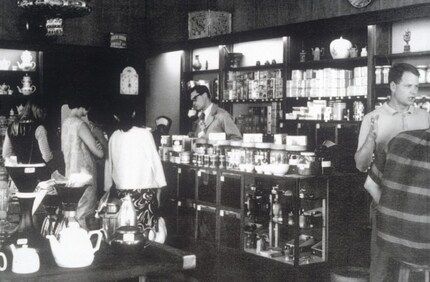

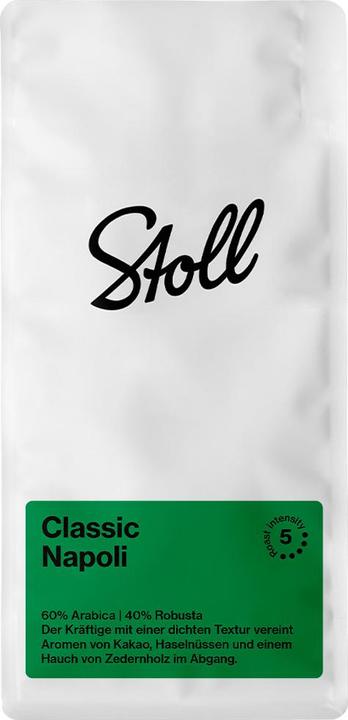

When people talk about coffee in Zurich, one always comes up: Shem Leupin, head roaster at Stoll and Swiss Coffee Champion 2013. «My first experiences as a barista were in Australia. Coffee was already huge over there. Looking back, they were just the first few steps. Then love brought me to Zurich and the rest is history.» He currently runs Coffee in Zurich’s Kreis 4 district alongside his role at Stoll. Over the last ten years, Leupin has worked with owners the Amann family to revamp Stoll's image. While the roastery used to primarily cater for gastronomy with beans for «café crème» from the automated coffee machine, the current range has been extended by more than a dozen varieties. «Our classics are still available, virtually unchanged. Our house blend, Roma and Napoli are certainly in that category,» explains Shem Leupin. New additions include organic coffees from different growing regions – all 100% arabica – where the beans only come from one plantation or cooperative. «Speciality coffees» are of very high quality, fruity and have a unique character that also only comes from one plantation or cooperative. These small series are mainly bought by aficionados direct from the roastery. «We're also extremely proud of our coffee capsules,» says Leupin. «They're the only ones on the market that you can put in your household compost. All the others call themselves compostable, but that just applies to industrial compost, meaning green waste.»

Stoll Kaffee Napoli

500 g, Dark roast

Stoll Kaffee Bolivia Organic

25 x Port.

Unlike Stoll's single café, ViCafe has espresso bars all over the city, which sell beans as well as coffees. All of them sell their coffee through a window on the pavement. «It's part of the concept,» explains managing director Ramon Schalch. ViCafe originally emerged in Eglisau in the canton of Zurich from the Vivi Kola brand, which was revived in 2010. The founders bought a coffee roaster to be able to offer their own coffee at Vivi Kola Bar in Eglisau. «Founder Christian Forrer knew early on that cola alone wasn't enough to keep customers in the bar,» explains Schalch. «After four years, he decided to separate the products. The coffee business was renamed ViCafe.» The concept works. Their coffee windows are in all the best spots, such as Bahnhofstrasse, Bellevue and Münsterhof, and are mostly recognisable by their long queues.

«We influence the entire value chain but we also depend on it. If you're buying wine, you can't go far wrong. If the wine's bad, either the winemaker has got something wrong or you've stored it incorrectly. We, on the other hand, buy green beans direct from the farmers. They can make mistakes with drying or fermenting the beans. Things can also go wrong with transportation, and that's all before the coffee has even been roasted,» explains Schalch. «Finally, however, it reaches the barista. Who can still mess it up seconds before it's sold.» Shem Leupin from Stoll agrees. «Before the coffee sacks go on the ship, the supplier sends a sample of the green beans by post. We can then roast them and compare them with the beans that have been on the ship for a few weeks.» This ensures that the beans have arrived in Zurich unaltered. Bad weather during transportation can damage the beans, but they can also be mixed up or intentionally replaced with bad coffee. «If it says arabica, it has to be arabica. We'll notice straight away if something's not right,» says Leupin.

Arabica vs. robusta

There are two well-known kinds of coffee: arabica and robusta (also known as canephora). While arabica is harder to grow and maintain, robusta is, well...robuster! Who'd have thought it? Arabica is milder, more aromatic and more harmonious. The small beans contain up to 800 different aromas, from citrus to floral and caramel notes. Robusta beans have fewer coffee oils and a different genetic source, which is why they taste completely different. Earthy, nutty and even tyre rubber aromas have been attributed to robusta. That's why comparing coffee beans is like comparing apples and oranges. It's impossible. Roaster Shem Leupin generally prefers arabica because robusta tastes much sourer and more bitter. «However, this is exactly what many people want, which is why our classic coffee blends always have some robusta in them,» he adds. Dark Italian roasts often contain a proportion of robusta. 100% robusta roasts were seen as undrinkable up until the third wave. The «fine robusta» trend has emerged in recent years, giving the maligned plants the same attention as their more illustrious brother arabica. New genetic mixes and better growing regions should wake the robusta from its deep sleep. A questionable advantage: climate change is making growing arabica more and more difficult and an increasingly number of growing regions are dropping out of existence. This could leave a gap for robusta to fill.

Shem himself mainly drinks filter coffee because it's the best way to allow the aromas to develop. This doesn't have much to do with the ditchwater of the first wave. The preparation is like working in a lab. Coffee and water are weighed down to the gram and the temperature and brewing time are crucial (in German). Shem leaves nothing to chance with espresso either. «I never make espresso without scales!»

Pioneers like Ramon Schalch and Shem Leupin have brought the third wave to Switzerland with their gastronomic concepts and roasteries. Coffee has become a household hobby. Coffee mills and portafilters are replacing automated machines and Nespresso. Whether it's super cheap filter coffee ground by hand or made using top-of-the-range equipment costing as much as a small car, coffee is accessible to everyone. «The main thing with coffee is that you have fun and discover the flavours. Then you'll learn quickly!» explains Leupin. It's never too late to get into it, as «the third wave has only just started, it's still a small movement in Switzerland,» adds Ramon Schalch from ViCafe. «In Australia, Starbucks is withdrawing more and more and surrendering territory to smaller coffee shops.» Switzerland still has a way to go. The coffee mills are grinding slowly, but they're grinding all the same.

You can read more about the history of Nespresso in this feature (in German) in the Tagesanzeiger. Just so you know, the article's behind a paywall.

When I flew the family nest over 15 years ago, I suddenly had to cook for myself. But it wasn’t long until this necessity became a virtue. Today, rattling those pots and pans is a fundamental part of my life. I’m a true foodie and devour everything from junk food to star-awarded cuisine. Literally. I eat way too fast.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all