Caesarean section deficits can be compensated for by breastfeeding

For a long time, it was thought that babies born by caesarean section were at a disadvantage. A study from the Netherlands has now come to a different conclusion.

Increased risk of allergies, asthma or obesity - doctors have always warned of the negative consequences that a caesarean birth can have. The reason: during a natural birth, the baby comes into contact with important bacteria from the mother's vaginal or intestinal secretions. These bacteria colonise the newborn's intestines and become part of the newborn's microbiome.

The microbiome - the entirety of all microorganisms that colonise humans - is involved in vital physiological processes such as digestion. The initial colonisation by the mother's microbes is considered to be particularly important: studies have shown that caesarean section babies have a different intestinal flora to vaginally born babies. It was therefore assumed that caesarean section babies have a deficit of microorganisms.

Study with 120 mother-child pairs

Further investigations are necessary

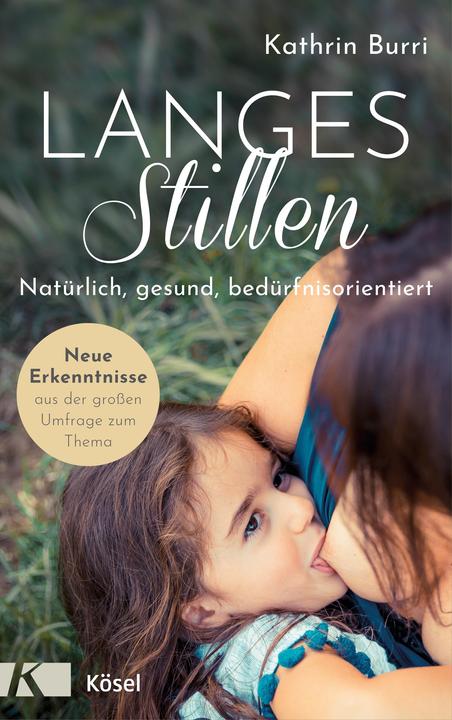

Cover photo: Unsplash/Wren MeinbergA true local journalist with a secret soft spot for German pop music. Mum of two boys, a dog and about 400 toy cars in all shapes and colours. I always enjoy travelling, reading and go to concerts, too.

From the latest iPhone to the return of 80s fashion. The editorial team will help you make sense of it all.

Show all