Pulsar’s Merger LRF XL50 thermal imaging binoculars have changed my relationship with nighttime hunting

These thermal imaging binoculars will be accompanying me through big-game hunting season in Graubünden. Can I turn darkness and dawn into my hunting helpers? Or will the Merger LRF XL50 even prove to be a gamechanger that revolutionises the way I hunt? The short answer is: yes.

I’ve been a hunter since 2014. To get to certain posts, I need to set off in the early hours of the morning while it’s still dark. It’s the only way I’m able to hunt animals active at dusk and dawn. Darkness has never been a good hunting companion for me. In fact, it’s often led me to send animals fleeing into the night by mistake.

The canton of Graubünden has allowed the use of thermal imaging devices for several years now. Could this be the answer to all my problems? In a bid to find out, I put the Merger LRF XL50 through its paces.

Box contents and first attempts

For the latter half of big-game hunting season in Graubündnen, I’m given a Pulsar thermal imaging device to try out. I’m intrigued. The day before the hunt, I take the device out of its box and see what else is inside.

Source: Claudio Viecelli

Here’s what’s in the box:

- Merger thermal imaging binoculars

- Battery

- Battery charger

- Power adapter

- USB-C cable with type-A adapter

- Storage bag

- Neck strap

- Tripod adapter

My alarm goes off at 5 a.m.: reveille. I get up and light a fire, the cold palpable in the morning air. After making myself a coffee, I read the brief set of instructions in front of the fire. There are six push buttons on the thermal binoculars, so I take a moment to memorise their functions – it’s not like I can fiddle around with them during the hunt.

The blue button on the right side is used to switch on the device and manually calibrate it. Calibration compensates for the background temperature of the microbolometer and irons out any image errors. Bolometers are devices that detect infrared radiation. When radiation hits a bolometer, a change in electrical resistance takes place. This is then measured and converted into temperature. An image is then produced based on this temperature change. The device can also self-calibrate automatically. In the middle, there’s a button for taking photos or videos. Above that, there’s the distance measurement button. On the left side of the thermal imaging binoculars, there’s the button for zooming and scrolling up and down, as well as the menu button.

Source: Claudio Viecelli

I then slot the battery pack into the middle of the device, gently pushing it in as far as it’ll go. The device comes to life. I take my first peek through the viewfinder. Anything cold in my surroundings appears in dark blue, while warmth shows up in red. The fire I lit earlier comes up in dark red. Time to figure out what settings I can configure in the menu.

The buttons are assigned multiple functions, determined by whether you’re doing a short- or a long press.

| Power button | Short press | Switches on the device or, if the device is already on, calibrates it. | Long press | Holding the button for 3 seconds turns off the device. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record button | Short press | Starts recording. | Long press | Switches from video- to photo mode. |

| Rangefinder button | Short press | Activates rangefinder or stops scan mode. | Long press | Activates scan mode. |

| Up/Zoom button | Short press | Magnifies zoom to 5X, 10X or 20X. In the quick- and main menus, the button is used to scroll up. | Long press | Switch Picture-in-Picture mode on and off. |

| Down button | Short press | Switches amplification levels and scrolls down when browsing the quick- and main menus. | Long press | Turns the White Hot palette on and off. |

| Main menu button | Short press | Opens the quick menu | Long press | Opens the main- or sub-menus. Closes the main menu. |

After a few minutes, the controls feel pretty intuitive. With the default, metric settings already good to go, I don’t make any adjustments to the settings. The feature I’m most interested in right now is the option to stream from the binoculars to my smartphone in real time. To do this, I need to download Stream Vision 2 from the App or Play store first. Once I’ve done that, I turn on the binoculars’ WiFi and pair them with my smartphone. They connect instantly, my smartphone displaying the image captured by the viewfinder in real time. Pretty cool. If you think about it, I could just grab the tripod adapter, stick the binoculars on a tripod outside, crawl back into my warm bed and keep watch via my smartphone. Alas, this wouldn’t be legal in Graubünden, so I quickly abandon the idea. Stream Vision 2 also gives me access to the device’s 64 GB internal memory, allowing me to transfer photos and videos to my smartphone. Pulsar also has a cloud where you can upload images and video footage, but I don’t use it.

Time to take a couple of snaps. I wonder how much heat’s being lost from this alpine hut?

Source: Claudio Viecelli

First hunting day

Now up to speed on everything the device can do, feeling full of optimism, I get dressed. Kitted out with provisions and a thermos flask of coffee, I head out into the darkness just after 6 in the morning. As I’m making my way to a nearby hunting post, I occasionally take a look at the edge of the forest using the thermal imaging binoculars. Everything’s dark blue; no discernible traces of heat, no sign of any game. I head back around noon, spending the next couple of hours eating lunch and reading. Once I’m done, I head back out to hunt, only to be met with a veil of fog.

Source: Claudio Viecelli

The visibility is just under 50 metres. According to the product description, the device can be used in extremely poor weather conditions too. As far as hunting is concerned, you don’t get much more extreme than this. Darkness and fog are a hunter’s worst enemies. For comparison, I take a photo with both the thermal imager and my smartphone.

Source: Claudio Viecelli

The thermal binoculars significantly improve my visibility. I’m impressed. Unfortunately, I don’t see any game in the evening either. In fact, two more days go by without a single sighting.

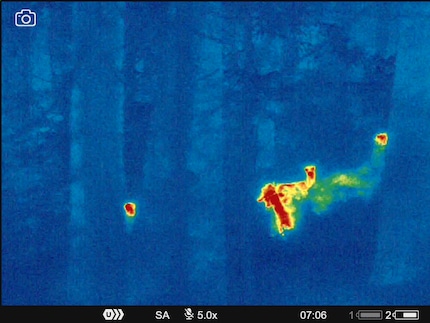

On my way to the post on the morning of 23 September, I suddenly see something in the early morning light. I hurriedly switch on my thermal imaging device. There, between two young spruce trees at the edge of the forest, are four deer. Unfortunately, they all jerk their heads in my direction, meaning they’ve noticed me first. A few seconds later, they run off.

Source: Claudio Viecelli

I’m still pretty chuffed. Seeing animals in the wild is always wonderful. It’s only 7:06 a.m. and it’s already shaping up to be a great day. My morning and evening watches go by without any further sightings.

The hunt continues

The next morning, I decide to journey to a hunting post we’ve christened «Hell». Set on very rough terrain, thick with alpine roses, tall grass, dense alder thickets and pockmarked with deep holes, the post is located about 1,800 metres above sea level. Hiking up there takes just under an hour. At around 6 a.m., I leave the hut and try to get my eyes used to the darkness. The steep path leads me through forests interspersed with small clearings and glades. It’s pitch dark, so I turn on my headlamp. I choose the dimmest setting, so that I’m at least able to see roots and stones on the path. I want to reach the post quietly, without being noticed. Every single footstep is carefully planned, helping me avoid any pine cones or small branches that might crack under my La Sportiva hiking shoes (I could write an ode to these shoes while I’m at it). The grass and moss are wet with dew, the scent of the forest and mushrooms in the air.

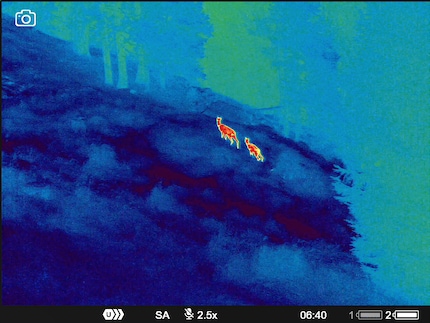

After almost 40 minutes of walking, the smell of deer suddenly hits me before I reach a clearing. I stop in my tracks. Is the smell just a result of wishful thinking, my imagination playing tricks on me? I steal my way over to the edge of the clearing and stop. Then, I turn on the Pulsar and take a look around. I freeze. There are two deer in the middle of the clearing.

Source: Claudio Viecelli

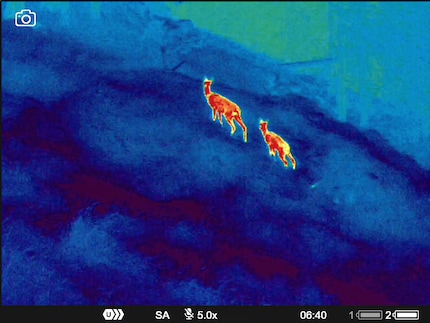

Under the cover of darkness, the animals look past me, unable to make out my silhouette. This gives me the opportunity to look at the animals in different magnifications. The range goes from 2.5x to 5x, to 10x, to 20x. Mind you, this is digital, not optical.

Source: Claudio Viecelli

Does and fawns are protected during hunting season in Graubünden, so I watch the animals through the thermal binoculars for another minute before setting off again. If they’d been huntable animals, I would’ve been able to wait there undetected until there was enough light to take a shot. Catching sight of a doe and fawn together is always pretty special to me. It shows that there’s a new generation growing up, a process I always find fascinating.

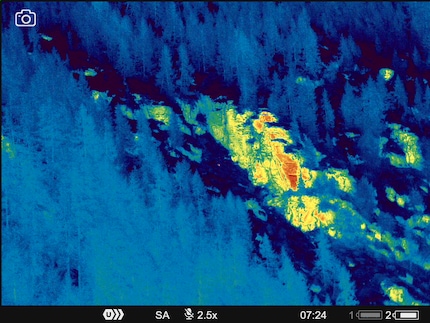

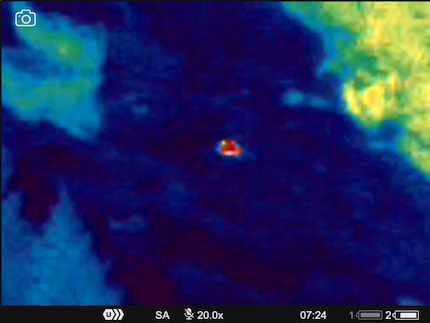

I make a pit stop before I reach Hell, digging out my Peltor SportTac Hunting hearing protectors and positioning them on my head. If there’s any huntable game near the post, I’ll just need to quickly pull the Peltor over my ears to be ready to shoot. Creeping my way through tall grass and alpine roses, I eventually get to the post. It’s a bit of an anticlimax. No traces of heat in the glades or at the forest edge. 517 metres away, I spot a heat signature through my thermal imaging binoculars. I grab my Zeiss binoculars, zooming in to 10x magnification to get a closer look. And sure enough, the little red spot turns out to be a lone doe.

Source: Claudio Viecelli

Source: Claudio Viecelli

I’d never have spotted the lone animal in the tall grass without thermal binoculars. I need to look through both sets of binoculars several times before I can see the creature in my Zeiss pair. For the next few minutes, I refuse to let the doe out of my sight. Is she really alone? Or does she have a fawn? If there’s no fawn, I’ll be free to hunt the doe. Her fur is greyish compared to other does in the area. Fawns are essentially always in sight, always in close proximity to their mothers. This doe is definitely on her own. After grazing, she moves towards me, heading into her den in the forest. Given we’re 1,800 metes above sea level and it still feels like 20 degrees Celcius, I don’t blame her. With no more sightings of the doe on the cards, I start making my way home at noon. From this day on, Pulsar’s thermal imaging becomes my constant companion.

I leave the hut earlier and earlier each morning, treating the dark as a helpful friend. Although I spot deer and their heat signatures at the forest edge multiple times on my forays into Hell, an opportunity to hunt never presents itself.

The final day of hunting

Big-game hunting season draws to a close in Graubünder on 30 September. The weather had been beautiful all week, culminating in a full moon on 29 September. Bascially, this meant my hunting conditions were suboptimal. With animals able to see even better at night, they’d rest during the day and eat at night to escape the hunting pressure. Undeterred, I set off for Hell one last time. Arriving at the post, I see...nothing! My last morning hunt of the Graubündner season and there’s nothing in sight. I spend the next two and a half hours mentally piecing this article together and going through my to-do list for the week. My head’s anywhere but the hunt.

At 9:24 a.m., there’s a doe starting to graze in the clearing, moving in from the left edge of the forest. The unusual colour of her fur catches my eye immediately. I’ve seen this animal before. It’s the lone doe I’d been watching a few days before. As a result, I know the animal is huntable and not lactating. I watch her through the scope; she’s grazing peacefully, occasionally casting a watchful eye down the valley. I run through my pre-firing checklist in my head. The doe is huntable, there’s a backstop and I’m able to recover the animal. I’m 100 metres away from my target and the wind isn’t an issue. The doe takes a delicate step forward and continues to graze. I really need to psych myself up to be able to shoot such a graceful animal. It’s my duty as a hunter to do this in an ethical way. And that’s only possible with a well-aimed shot through the chamber, leading to instant death.

I give thanks for this beautiful sight, the life of the animal and its meat. Then, slowly but surely, I pull the trigger. The animal falls sideways. As it’s on a slight slope, it rolls over and lands in an alder bush. I reload. The animal doesn’t move again. I’m trembling, seized by a deep sense of humility and gratitude, and need to pull myself together. Breathing deeply helps me to focus. I wait a few minutes, collecting my thoughts. Then, I gather up my stuff and make my way over to the animal. I tear off a few larch branches and prepare the animal’s last «meal» – a hunting custom which involves placing a twig in the mouth of the slain animal. I sit down next to the animal, in need of a few minutes of calm. Then, I pull out my smartphone, call Marco and tell him about the kill. I’ll need some help recovering the doe.

Verdict

Thanks in part to the Pulsar Merger LRF XL50, I was able to shoot a doe on the last day of hunting season in September. If I hadn’t spotted the animal with the device a few days earlier, I wouldn’t have been able to observe it, cementing the details of it in my mind. Nor would I have known that the doe didn’t have a fawn, and was therefore huntable.

Source: Claudio Viecelli

Regardless of how my last day of hunting went, I’d still have grown fond of the thermal imaging device. Since you can look through it with both eyes, it’s very comfortable – better than monocular devices, if you ask me. The thermal binoculars are also nice and light. Including the external 3,200 mAh battery, the device weighs in at 950 grammes. The capacity of the internal battery is 4,000 mAh and both batteries together allow for ten hours of thermal imaging detection. There are two charging options. You can either charge the external battery with the included battery charger, or charge both batteries together by hooking up a USB-C cable to a port on the thermal imager. The screen’s 1,024 × 768 pixel resolution provides a very clear picture.

Another cool feature is the proximity sensor, which can detect whether you’re looking through the binoculars. If you take the device away from your eyes, the display turns off. Not only does this save battery, but it also reduces the likelihood that an animal will spot you. Another important aspect for hunters is distance measurement. Directly linked to ballistics, it needs to be taken into account when firing a shot. In scan mode, you can scan the distance to a forest edge in a flash and get the exact distances back. As a result, I can quickly determine whether I’m within the legal shooting distance of 200 metres. With this thermal imaging equipment, I’m already looking forward to next year’s hunting season in Graubünden.

Header image: Claudio Viecelli

Molecular and Muscular Biologist. Researcher at ETH Zurich. Strength athlete.

These articles might also interest you

Background information

When the path becomes the goal - On the Grisons high hunt with two Pulsar thermal imaging devices

by Claudio Viecelli

Guide

Big game hunting: testing Pulsar thermal imaging devices in the Grisons mountains

by Claudio Viecelli

Product test

With sat nav for the night sky: the Celestron StarSense Explorer LT 70 AZ entry-level telescope

by Michael Restin