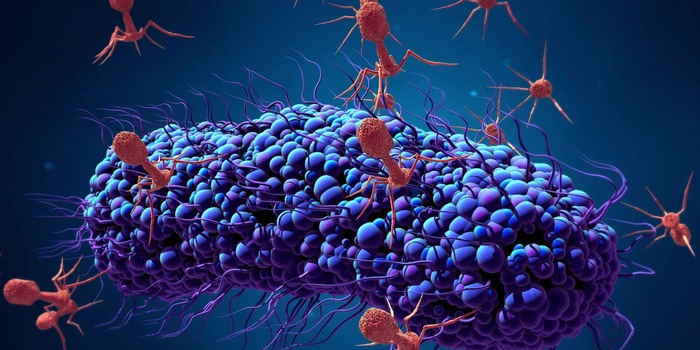

Bacterial toxin activates dormant viruses

The colorectal cancer-causing molecule colibactin turns out to be an insidious chemical-biological weapon. Bacteria in competitors use the substance to activate deadly viruses that cause the cell to burst.

The molecule colibactin, produced by many bacteria, reawakens viruses built into the genome. This was reported by a team led by Emily P. Balskus of Harvard University following experiments on bacteriophage-infected microorganisms, including those found in the human gut. As the team reports in Nature, inactive viruses - called prophages - built into the genetic material of bacteria become active again after contact with colibactin-producing bacteria, producing virus particles and destroying their host cell. In addition, the bacteriophages released in this way can destroy other bacteria. The team around Balskus therefore suspects that colibactin is used for "warfare" and possibly also has considerable effects on the composition of the human intestinal flora.

Colibactin is an unstable molecule that reacts with DNA and causes genetic damage - among other things, it is thus probably involved in the development of colon cancer. Until now, however, it was unknown what function the substance performs for the bacteria. Balskus and her team now suspect that bacteria use it to trigger epidemics among competing microbes. The ability of colibactin to damage the genome is crucial for its effect. Genetic damage triggers the SOS response in bacteria, an emergency program in which the cell stops growing and concentrates on repairing the damage to the DNA - but the SOS response is also the signal for prophages built into the genome to become active again.

The research group suspects that this insidious form of chemical-biological warfare is widespread. Not only do many bacteria produce the unstable molecule, the team also found resistance genes against it in bacteria that do not produce colibactin themselves. In addition, the toxin works in principle in almost all types of bacteria that have no specific resistance to it. Conversely, however, some factors limit the effects of the molecule so that its release does not lead to general phagocalypse in the entire bacterial ecosystem. For one thing, colibactin is very unstable, so that it is rapidly degraded. For another, Balskus' team showed that the attacking bacterium must touch its victim for the molecule to take effect - and the viruses released are too few to have a major impact. That is why colibactin, contrary to what it may seem at first, is probably primarily a close-range weapon.

Spectrum of Science

We are partner of Spektrum der Wissenschaft and want to make well-founded information more accessible to you. Follow Spektrum der Wissenschaft if you like the articles.

Originalartikel auf Spektrum.de

Titelbild: © Design Cells / Getty Images / iStock (Ausschnitt)

Experts from science and research report on the latest findings in their fields – competent, authentic and comprehensible.

From the latest iPhone to the return of 80s fashion. The editorial team will help you make sense of it all.

Show all