Opinion

Why you should stop using social media right now

by Oliver Herren

Amazon Alexa is upon us. The voice assistant has officially been launched in Switzerland. However: is she always listening? Or, in other words: how much does Alexa monitor you?

Amazon has brought Alexa to Switzerland. The smart voice assistant lives in your speakers and smartphones, all the while listening quietly whenever you say something. A massive concern in terms of data protection: Jeff Bezos is always there. He’ll know what you say to your cat and what’s being discussed at dinner. He’ll even be creeping on you during sex. Horrifying!

It’s hysteria and rational apprehension all in one, every smart device will spark new discussions.

Which I’m certainly very happy about.

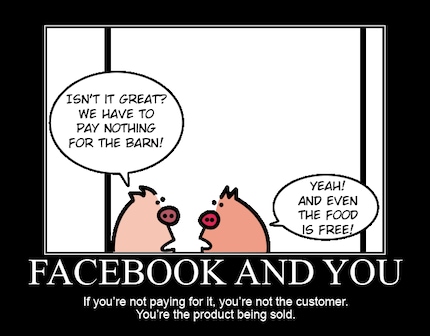

Data protection and privacy are being threatened by a new foe practically every week. This app wants more data, that one has you revealing something about yourself again. You’re trapped by the classic Internet warning, especially when it comes to free services such as Amazon’s Alexa: If it’s free, then you’re not the customer, you’re the product.

With Amazon Alexa, you’re the «product» being sold to «paying customers». Alexa, the voice assistant, is free. You can download the app for free from Apple’s App Store or the Google Play Store while paying for the actual device, say the Amazon Echo or Echo Dot, for example. You’re actually paying for the privilege of being traded as a product.

The Alexa app provides an initial indication of what exactly Alexa is listening to. You’re free to inspect every one of your voice commands Alexa has interpreted. The reason? If Alexa gives you an incorrect answer, you can say «No Alexa, you messed up» via the app, helping Amazon improve their service. Perpetually optimising the product harvested from you. This also allows Alexa to send your voice recordings overseas for analysis.

On a technological level, Alexa only listens when she hears the name «Alexa» after a short period of silence. So when you mention her name in conversation, she doesn’t respond.

After all, every device with a voice assistant has two separate «hearing circuits» installed, i.e. two systems that listen to you. They are named as follows.

The passive system is only there to respond to «Silence, Alexa.» No data is transferred. The passive system is local and read-only on Sonos One, as far as I can tell. According to several sources, you can change the trigger word on Echo devices. So if you have a cat named Alexa, then you need to rename either the cat or Amazon’s Assistant. You can’t do that on Sonos One.

When the passive system reacts, it triggers the active system. This is the part that records your voice and analyses it in the cloud. You can tell visually from the devices themselves. On Echo devices, a blue ring lights up, indicating «Attention: recording in progress.» However, since Alexa responds to all voices that say «Silence, Alexa», this can be fairly easily overridden.

My Sonos One Alexa activated at around 47 seconds into the above video. Then again at 1:04. Turns out Alexa has extremely sharp hearing. It’s stood in my living room, a few metres and doorways away from my bed. I can nevertheless give commands at normal conversational volume, and Alexa responds correctly. How well Alexa hears depends on how good her microphones are. It’s quite possible that Sonos has installed better microphones than Amazon in its Echo Dots.

So if I record a voice command of me saying «Alexa, buy a Breguet» and run it in your home, Alexa will respond, assuming you have all the purchase and delivery information correctly on file with Amazon.

Alexa doesn’t always listen.

But she listens to her name. So if you have a cat named Alexa, you’ll already have a problem. Or if you yourself are called Alexandra, nicknamed Alexa.

There are currently 100 million, or 100,000,000, Alexa devices worldwide according to Marketingland. Now, if these devices were listening 24 hours a day, they would quickly amass an enormous amount of data.

Accordingly, all Alexa devices would produce 144,000,000 MB of data. Every. Day. That would be 144,000 terabytes or 144 petabytes. Let’s compare: statistically, your laptop probably has about half a terabyte of memory.

Amazon would then have to listen through this incredible amount of data, or so the myth goes. According to some horror stories, this is actually happening right now. Conjuring up dystopian images of huge offices filled to the brim with employees, all wearing headsets, just listening to what users say and taking notes of what they hear. Just in case anything noteworthy pops up.

This surveillance apparatus, regardless of the amount of data in petabytes, cannot exist. After all, no matter the type of audio surveillance, you require one listener per speaker. Simply put: Amazon would have to have one employee per user packed into this hellish vision of an open-plan office. That would mean 100 million employees per 100 million users. However, according to its own data, Amazon has 298,000 employees worldwide. If all these people were to do nothing but listen to users, they’d only manage to continuously monitor 43,267 users for three eight-hour shifts each.

They could manage more if Amazon filtered out silence via artificial intelligence.

Still, there’s a chance that an Amazon employee somewhere is listening to your Alexa recordings. Back in 2019, Time Magazine revealed that thousands of Amazon employees worldwide were listening to selected Alexa clips. All to improve Alexa’s artificial intelligence, apparently. After all, it doesn’t automatically understand every dialect and can’t automatically distinguish between all background noise and commands. She has to be taught. How is this easier than with real-world examples?

If an Amazon employee is listening, here’s how it goes, according to Time Magazine’s sources: in nine-hour shifts, employees around the world transcribe recordings and feed them back to Alexa. To do this, the software receives annotations from the transcribers so it can better understand what exactly happened.

This army of listeners isn’t only directly employed by Amazon, but can be provided by contractors. These employees and contractors work in the USA, Costa Rica, India and Romania. Per shift, a person hears about 1000 recordings, all following the «Alexa» command.

One employee reports spending hours on the words «Taylor» and «Swift.» They taught Alexa’s software when a user produced «Taylor» – either the name or a homonym for «tailor» – or «Swift» – as in «fast» or «hurried» – in a different context, or whether the user was actually referring to singer Taylor Swift.

Other employees report an internal chat used to share funny or horrible recordings. Sometimes it’s «a woman singing badly off key in the shower», other times it contains «a child screaming for help». Amazon has specific guidelines on how employees should handle hearing something like a cry for help or conspiracy to commit a crime. Two employees from Romania say, «[…] it wasn’t Amazon’s job to interfere».

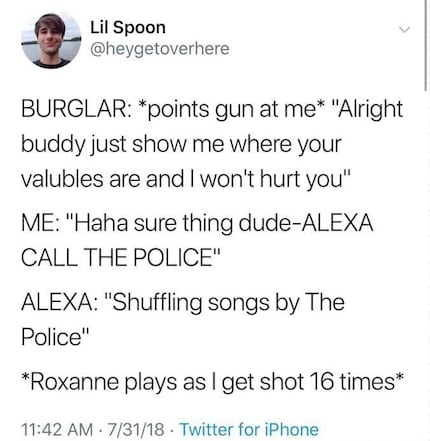

This way, Amazon is preemptively fending off a wiretapping scandal. The corporation can listen to you – you’ve already agreed to that if you have an Alexa according to their terms and conditions – but it cannot react outside of a specific command. If you’re getting physically abused by your partner and Alexa happens to be listening, no Costa Rican employee is going to inform the Bern city police that you need help. But «Alexa, call the Police» will put out an emergency call.

Couldn’t Amazon do a lot of good with an emergency monitoring device? Definitely. But interacting with your life outside of explicit commands may not be in a large corporation’s wheelhouse.

Amazon itself responded to Time Magazine in 2019. While people are listening, the group has no information about who the people in the recordings are, they said. Data is anonymised.

In the app’s settings, you can turn off data sharing for analytics and development purposes. Which I recommend you do. This is, by the way, better than the «This call may be recorded for training purposes» line you’ll hear out of any call centre. With them, you only get to choose between «Monitored customer service» or «Leave me alone, dude.»

Another big but: you’ll often receive advertisements about things that you mentioned in conversations with your mother, let’s say. Or referring to that new cat toy you mentioned to your pet at dinner. Your cat answers with «Meow», then the Internet butts in with «Buy now!» However, this isn’t due to your smart speaker, be it Alexa, HomePod or Google Mini, but a completely different mechanism.

After all, Alexa isn’t the only thing spying on you. The Internet as a whole has been checking on you for years. Third-party cookies and their successors analyse your browsing behaviour. Apple recently started putting a stop to this, and did Google.

The chances that you’re talking to your cat about the same thing you’re looking at online are pretty high. Such as the latest Zalando t-shirt, stylish as it may be. That new purple iPhone. Or even another cat toy, with your furry friend quickly destroying anything it gets in contact with. Your browsers remember all of this, abstract it, and form a supposed user profile. If you’re ordering cat food, they’re pretty sure you’ll be interested in cat toys. After all, statisticians and thus the advertising industry know: cats destroy toys. Therefore, the leap from ordering cat food to cat toys isn’t far.

Add to that our own stupid brains and the concept of confirmation bias. It states that you, consciously or unconsciously, will gather or arrange information in such a way that it confirms your opinion. In the case of Amazon Alexa, you’re looking for confirmation that she’s listening to you. So you pay attention to your conversations. You know Amazon is listening to you, but you forget what you searched for before… As a result, you remember telling the cat that she’s the «dumbest furball ever» because she «destroyed her stuffed mouse again». So now when you see ads for plush mice, there it is: proof that Amazon’s Alexa is monitoring you! Meanwhile, the countless ads for NordVPN, Raycon headphones or «Raid Shadow Legends» you also got displayed are all simply ignored, tuned out by your brain.

Nevertheless, maybe sometimes, for once, it’s not confirmation bias. Amazon can change its terms and conditions. They can customise the software and have Alexa always listen and give itself the right to always listen. Although this seems unlikely at the moment, the possibility is still there. All that is needed for permanent monitoring is a decision from Amazon’s upper management. Be it due to plummeting profits or the fact that they’ve become moustache-twirling villains after all.

This is exactly why privacy questions should never stop being asked. And why you and I and our parents and all other potential users should keep asking ourselves what data the latest popular product is trying to get at. Because even if there’s hype around Alexa: in the end, she listens to you and sends your voice to huge data storage centres all over the world. She may not listen as often as some people think, but somewhere in Romania, someone may be listening to you talk to your kitty about catnip and your boss.

By the way, the cover image above is from srlabs.de.

Journalist. Author. Hacker. A storyteller searching for boundaries, secrets and taboos – putting the world to paper. Not because I can but because I can’t not.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all

Background information

by Michael Restin

Background information

by Katherine Martin

Background information

by Michael Restin