Background information

Why the 10-per-cent rule in jogging is actually wrong

by Siri Schubert

Those who are born with the right genes have a decisive advantage in sprinting. Just one look at the knees tells you whether someone can run best times. Not only on two legs.

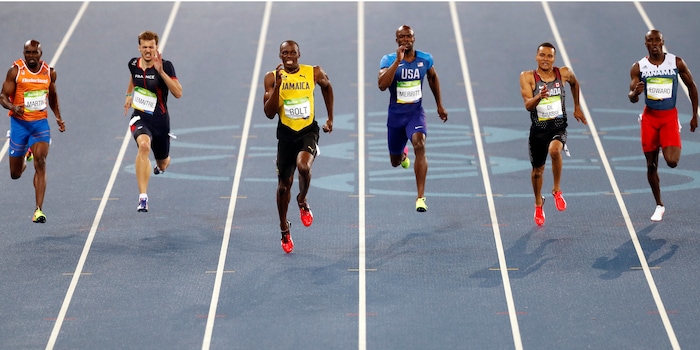

Usain Bolt is the best - and thus probably the best example. The fastest sprinter ever to race across the world's tartan tracks cultivated the image of the easy-going bon vivant who chased record after record with a smile and a moderately healthy diet. The Bolt show concealed the fact that it was not only extraordinary talent paired with physical advantages, but also extreme training that lay behind it. With his long legs, he practically flew to the finish, needing on average three steps less for the 100 metres than his mostly smaller competitors.

But it's not just him. His small homeland Jamaica produces rows and rows of top sprinters. Despite criticism of the tough funding system and a general suspicion of doping that always runs in athletics, one thing is clear: fast people live there. With a high proportion of "fast" type IIb muscle fibres and other assets that ensure that athletes from other parts of the world mostly only see them from behind. This makes the sprinter's island interesting for science.

While some are tracking the "speed gene" ACTN3 or determining that people of West African origin (which applies to much of Jamaica's population)have over eight per cent more type II muscle fibres, a team led by evolutionary biologist Robert Trivers took a different, and at first glance simple, approach: The researchers took a very close look at the lower extremities and measured them.

In a long-term study in 1996, 288 Jamaican children aged five to eleven were measured for body symmetry, which included knee and ankle width and foot length on the legs. Ten years later, they underwent this procedure again as adolescents, and 14 years after the first measurement, 163 of them took a sprint test as young adults.

It was mainly those with high symmetry values who felt like taking this test at all. And those who competed with symmetrical knees were particularly fast. This seems logical and efficient when it comes to running fast in a straight line. Nevertheless, the researchers were surprised by this clear correlation, which immediately jumped out as statistically significant. So they set about measuring some of the best runners in the country (and thus the world) after this untrained group.

Not surprisingly, the athletes' knees were also more symmetrical than those of the control group from the normal population. 30 of the 74 in total specialised in the 100 metres and had the most "perfect" knees, with those of the fastest athletes among this sprinting elite again being the most symmetrical. In the case of three-time Olympic and ten-time world champion Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce, there was virtually no difference between right and left.

The ankles were also strikingly symmetrical in the 100-metre specialists. The feet, on the other hand, did not play any particular role. Those who ran longer distances and thus curves were not quite so similar at the knees and especially at the ankles.

This raises the question of whether these features are a result of training or quasi-inherent. As far as the knees are concerned, the long-term study with the children suggests that it is possible to tell early on who will be fast later on. Presumably this is true not only in Jamaica, although similar data from other parts of the world are lacking.

Generally, symmetry is something we not only find instinctively attractive, but by all accounts it is also useful from an athletic point of view. Even when it comes to symmetrical ears and nostrils, which have been linked to better middle-distance running performance. Similar associations have also been found in racehorses.

As fascinating and symmetrical as the sprinting performances of world-class female athletes are: Compared to the animal kingdom, even Bolt's 44.72 km/h top speed is rather lame. Even a domestic cat gets to 48 km/h and larger quadrupeds are completely out of reach. To keep up, we humans usually come up with technical solutions. For example, an exoskeleton with a spring that would theoretically have accelerated Bolt to over 70 km/h during his world-record run.

Maybe the future of sprinting leads back to nature, though. On all fours. A study seriously hypothesises that at the 2048 Olympics, the winner of the 100 metres could gallop to the finish line on hands and feet in 9.276 seconds, beating the fastest biped (9.383 seconds). For this, the athletes would have to orientate themselves less on the galloping technique of horses and more on the cheetah or greyhound. Not everything is symmetrical. Some things are also simply oblique.

Titelbild: Salty View / Shutterstock.com

Simple writer and dad of two who likes to be on the move, wading through everyday family life. Juggling several balls, I'll occasionally drop one. It could be a ball, or a remark. Or both.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all