Background information

The Matrix in IMAX – ready for the red pill?

by Luca Fontana

Ten years after it premiered, Interstellar is returning to IMAX cinemas. And with it, the questions that never lost their grip on us. Questions about time, love, loss and what we’re truly left with at the end of it all.

I still remember the way I was sitting in the movie theatre. Fingers digging into the armrests, heart somewhere between the stars. And that organ music vibrating through my chest. Interstellar wasn’t a film you simply watched. It was an experience. Something that knocked you for six. If I can get spiritual for a second, it was also a prayer for the future – and for the things we hope to save.

Perhaps it was also a prayer for things we’ve already lost.

Now, Interstellar’s making a comeback. But not just any comeback. Instead, it’s returning to its true home – the biggest screen there is. IMAX. In English. And unless you see it in Geneva, without subtitles. By the way, this is all thanks to you. Interstellar won our poll by a landslide. It was almost as if the universe itself had voted.

So, on 22 June, we’ll be blasting off into interstellar realms together. That is, into every Pathé IMAX cinema in Switzerland. The screenings are being organised in collaboration with The Ones We Love and Pathé Switzerland. Here’s where you can get tickets for:

However, I’m not just writing this to give you a heads-up about the presale. It’s actually more of a love letter. An attempt to more intimately understand a film that still has us in its clutches. So sit back, stick on Hans Zimmer’s score and enjoy the article.

Caution: spoilers ahead.

There it is. Our earth. A pale, blue dot in the darkness. If you’re far away enough, it’s hardly recognisable. No continents, no borders, no noise. Just a pinprick of light, drifting its lonely way through the cold cosmos.

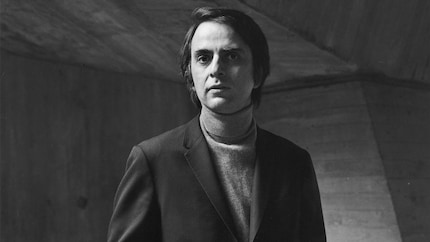

The famous photo depicting this dot was almost never taken. In 1990, the Voyager 1 space probe had already flown past all the planets in the solar system, and was ready to head into interstellar nothingness forever. Nobody at NASA saw any practical use in reactivating the camera. Especially not to take a pointless, blurry photo of the earth.

Nobody, that is, but Carl Sagan.

The astronomer, author, poet and longtime mediator between science and humanity fought for years to ensure this very image was taken. Not for research, but for us. As a message to future generations, as a reminder and for a sense of perspective. Photographed from a distance of almost six billion kilometres, caught in a strip of light, the earth was barely more than half a pixel in size.

«Look at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us,» Sagan later wrote of the photograph. «On it, everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you’ve ever heard of and every human being who ever was, lived out their lives.»

Is Interstellar about this dot? Is it about saving humanity? About a dying planet, barren fields and dust settling into every pore like a slow death? That’s what the synopsis says anyway. The lands on the pale blue dot have lost their fertility – and humanity has lost its future. Not because of an apocalyptic fire, but because of creeping suffocation.

However, this is only half the story.

In reality, it’s not just humanity itself that’s at stake – it’s the belief in humanity. The hope that, despite all our faults, the human race is worth preserving. That we’re beings capable of love.

At least that’s what Nolan tells us in his masterpiece of wormholes, quantum physics and gravity. Rather than the whole of humanity being the focus of this film, it’s a child representing it. Murph. And a father forced to leave his daughter behind in order to give her a future.

This is the very bet that Interstellar makes. It wagers that love – not technology, strategy or logic – will ultimately be the vehicle that carries us through space and time. Not because love is magical. Quite the opposite. Nolan postulates that it’s tangible. That it bonds us. Even over unimaginably long distances. Even when the universe is falling apart around us.

Maybe this is the silent message amongst the loud spectacle of Interstellar; that even the palest dot in space can be a place worth fighting for if someone we love is waiting there. Maybe, if we listen carefully, we’ll still be able to hear it – the organ music vibrating through our hearts. And it’ll remind us that even in the emptiest of spaces, we’re never completely alone.

That’s what this film’s about – and nothing less.

There’s this scene in Interstellar that doesn’t simply play out in front of your eyes. Instead, it burns itself into your memory. Not because it’s spectacular. There’s no spaceship blasting off, no wormhole opening up. And yet, it’s potentially the most powerful scene in the movie.

Cooper’s sitting there in a small, spartan room on board Endurance. He’s returned to the main capsule after a momentous mission on a planet where minutes turn into years. For him, only a few hours have gone by. On earth, it’s been 23 years. A crew member says, «There’s years of messages here.» Then, Cooper turns on the screen.

And there they are. His children.

Tom appears first. Still a boy. He talks about football practice, his grandfather and Murph. Then his voice deepens. He talks about high school. The death of his grandfather. Their dying farm. His own child. The years fly by. His hair changes. His voice grows harsher. Wrinkles appear on his skin.

Cooper doesn’t say a word. He simply watches as the time he’s missed comes crashing down on him like a series of punches. He gulps. Trembles. Eventually, he breaks down. The sound cuts. There’s no score. Just his breathing. His sobs. Until Hans Zimmer’s organ eventually returns. The resonating more deeply with every note – like the echo of a broken promise.

Then, Murph appears.

She hasn’t spoken to Cooper since he left. But now, here she is. An adult, of course. And hurt. She never actually wanted to send him a message. «But today’s my birthday,» she says, «And it’s a special one because you once told me that when you came back, we might be the same age. And today I’m the age you were when you left.»

It’s not purely an accusation. Not just anger. That one sentence carries everything. Hope, pain, loss, love. And an infinitely sad question: «Where have you been, Dad?»

That moment reveals what time really is. It’s not numbers on a clock. Not years. It’s missed opportunities for closeness. Hugs never given. Birthdays never celebrated. It’s not being able to see one another. In that one scene, Nolan sums up everything that makes Interstellar so unbearably human. It’s not the impending death of humanity, but the death of a moment that can’t ever be retrieved.

Which is exactly why that scene hits us like a meteorite. We all have somebody that we miss. We all know what it feels like not to have been there with someone – or to have been there too late.

It might actually be the truest moment in the film. Not an image of outer space, a black hole or a scientific monologue. But a man sitting in front of a screen, forced to watch the life he loves go on without him.

A father. A daughter.

And 23 years of silence between them.

A pale, blue dot in the darkness. That’s what our earth looks like when you’re far away enough. A tiny light in an infinite, cold cosmos. This is exactly where Interstellar begins. And it’s exactly where Nolan wants us to return. To ourselves.

You see, however far away he catapults his characters – into wormholes, black holes, water planets and frozen ice worlds – he still circles back to a deeply human question: what will we do if everything falls apart? If the planet’s dying, the dust is eating our crops and time is working against us?

The answer is: we’ll search.

Not for new planets, but for hope and connection.

Christopher Nolan’s film isn’t a space opera. It’s a father-daughter drama dressed as an astrophysics thriller. Yes, it’s got rocket launches and the theory of relativity. But at its core, it’s about a promise. About the love of a father forced to leave his daughter behind in the hope that she’ll never forget him. And whether that love is strong enough to break through space and time.

That’s big. Daring. And sometimes downright overambitious. But it works. Because Nolan has managed to reflect the biggest things in the smallest.

In the pale blue dot.

I write about technology as if it were cinema, and about films as if they were real life. Between bits and blockbusters, I’m after stories that move people, not just generate clicks. And yes – sometimes I listen to film scores louder than I probably should.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all