Opinion

5 years of "Baldur's Gate 3": Why the game remains an unrepeatable masterpiece

by Rainer Etzweiler

The World Cup in Qatar has officially got the ball rolling once again, bringing in a whole lot of cash – or more specifically, riyals. The desert state is all about fame and glory. And plenty of profits most of all. The whole thing leaves me with a bad taste in my mouth.

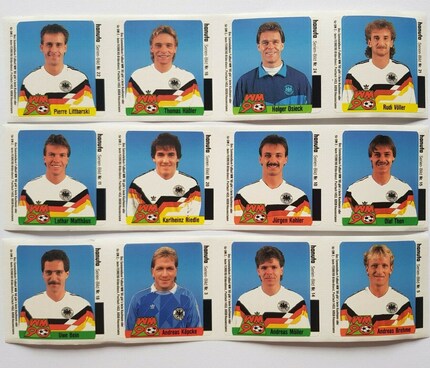

Spring 1990, Germany. I’m eleven years old and eating way too much Hanuta, Ferrero’s chocolate-hazelnut wafers. Rudi Völler is to blame. After all, I have to complete my Ferrero scrapbook before the World Cup in Italy starts. And I’m only missing one more player. One out of 30 stickers. They’re included in every Duplo bar and Hanuta pack for 30 pfennigs. A candy plus stickers at that price – as a boy, it seems like a better investment than the Panini scrapbook craze.

Today, children, or rather their parents, spend hundreds of francs and euros on stickers, just to fill a Panini album. Kids walk around sporting a Cristiano Ronaldo hairstyle, they celebrate their goals just like Kilian Mbappe. They adore PSG, Real Madrid or Manchester City.

Things were very different in my day. Back then… football was still real. Following a discussion surrounding the World Cup in our newsroom recently, I dreamt about football the following night. A sport that shaped my life for many years. It was a sobering experience. We had grown apart. Was it my fault? Or is football to blame? An attempt at reconciliation in 5 parts.

Back in the 1980s, my small Franconian village didn’t have much to offer: church, fire department, football field. My parents sent me to the local sports club. I was around eight years old the first time I laced up my shoes there. Training on a clay court, playing league games on grass – if the groundsman was in a good mood. Sometimes we’d win, but even when we conceded twelve goals in a game, we still kept going. Our coach felt that I was most valuable to the team in positions where I could disrupt or even destroy the opponent’s game.

Through diligent training, I was able to partially compensate for my lack of talent over the years. At 15, I was allowed to help out in the team for the next age group up. Their captain pushed me to perhaps the best performance of my soccer career. We beat some heavy favourite in the rain and mud.

My love for football had never been greater. On Bundesliga match days, I voluntarily washed the family car on Saturday afternoons just so I could listen to games over the radio. My favourite club, 1. FC Nürnberg, perpetually fought to avoid relegation. Even national team goalkeeper Andreas Köpke and the creative duo of magic mouse Zarate and magic foot Alain Sutter didn’t change much. F. C. Bayern München became champion, but in the 1990s other clubs also won titles every so often. The «Champions League» was still the «European Cup» in the minds of the fans.

At 18, I switched to the men’s division. The coach was hardcore, feared throughout our entire football district. He rushed us up hills, made us run endless laps around the pitch and forced us to carry our teammates. I’ve never been so fit in my life. In a few pre-season games, I was nominated to the first team. In the end, it wasn’t enough – I was sent to the second team, where the most important thing was sharing a beer following the final whistle.

During this time, my club urgently needed referees to avoid league penalties. I was asked whether I’d want to be a ref. It appeared my talent on the pitch was negligible. I accepted, completed the course and test, refereed a few youth league games, then seniors, and finally the upper division. A higher level than I could ever have played on. Alone or in a team, we’d travel to football fields all over Bavaria twice every weekend. I’ve never devoted more of my free time to football.

This was football in its purest form. Where true passion arises. Where a local bricklayer and lawyer give their all every Sunday in the amateur league, battling the neighbouring village. Where spectators comment loudly on what is happening on the pitch. Where, after the final whistle, both teams gather again on the pitch and process the game with beer and bratwurst.

I felt I had a small part to play in that. As a referee, I was a kind of moderator on the pitch. Calming hotheads, adjusting the game’s flow, enforcing rules. As a referee, I sometimes decided on promotion or relegation. I experienced a similar thing. A referee’s conduct was evaluated too. At the end of the season, grades would determine whether you’d qualify for a higher league. I never quite reached the top. But I didn’t blame football.

In 2008, I hung up the whistle. Two dozen referee jerseys ended up in the charity shop. Work and family were my new priorities. But I remained faithful to football as a spectator and observer. For a while, at least.

In 2007, «my club» won another title. 1. FC Nürnberg won the German Cup. And was relegated from the Bundesliga just as quickly the following season. During this time, I also visited the local stadium to watch some games. Changes were already taking place back then, it was all becoming one big show. Any time there was a corner kick, the stadium loudspeakers would blare out some slogan for the local beer accompanied by the crisp fizz of a freshly opened bottle. In general, everything was suddenly presented by someone: the number of spectators, player of the match, stretchering off an injured player.

The «Champions League» was being hyped more and more, it feels like today even a perpetual third-placed team from Lithuania is still allowed to participate in the preliminary qualifiers. If the team doesn’t make it, there’s the Europa League, once the proud UEFA Cup – and to give even more clubs from even smaller leagues their European football experience, there’s the Conference League even further down the ladder. More games, more money. That’s how it’s been for years. The Bundesliga radio conference on Saturday became irrelevant, as games were spread over more and more different kick-off times. For pay-TV providers, on the other hand, it was the key to unlocking more and more paying customers, offering increasingly expensive subscriptions for live broadcasts from Friday to Sunday. Clubs went along with it, their profits increasing as a result of TV licence sales. Stadium fans who bought their seat at the ticket office became more and more insignificant in relation. Nevertheless, they still had to take abuse for not continuing to provide a great atmosphere – take what happened at F. C. Bayern Munich:

Spectators had obviously become a tool for football bosses, serving as a backdrop to optimise TV revenue at will.

In 2008, FIFA announced the hosts for the 2018 and 2022 World Cups in one fell swoop. Russia and Qatar. At the time, Putin was still a «squeaky clean democratic president» to some, but his government wasn’t beyond reproach either. And Qatar… well, that was a slap in the face for anyone who loves football. Football in the desert makes as much sense as selling Ice cubes in Antarctica, and everyone knew it. But hey, I’m sure the decision really came down to corruption other factors.

Before Infantino, there was a brief glimmer of hope. Sepp Blatter had just stepped down as head of FIFA. Was awarding the most important football tournament to such unsuitable candidates simply the work of one corrupt crony? Had football not lost its heart after all? Nope. The 2010 World Cup in South Africa and the 2014 World Cup in Brazil proved it: FIFA has always only been concerned with its own image. More and more, backroom officials determined what this one-of-a-kind event would look like. Social unrest in surrounding areas? Oh no, how unsightly. During games, cameramen were no longer allowed to show streakers, nor obscene gestures from fans. Instead, directors had to gloss over such embarrassments with images of smiling fans, preferably female and blond. The fact that even the sale of specific beers is regulated in stadiums is almost no longer noticeable.

Not only FIFA had gone crazy. In Europe, filthy rich oligarchs went on a shopping spree. They took over entire clubs for billions, pumping millions into teams. Granted, the 1. FC Nürnberg – whose story I know best – wasn’t that different: its president, a carpet dealer in his main profession, would grant the club loans from his fortune on occasion. But this pales in comparison to the behaviour of Russian oligarchs and Arab emirs. In 2017, Neymar moved from FC Barcelona to Paris St Germain – for an absolutely bonkers 222 million euros. At least that was the official sum, somehow still compatible with «Financial Fairplay» rules. There was probably a whole lot more money flowing behind the scenes, paid for by the Qatari Ministry of Tourism. Qatar simply wanted the superstar at «his» club, PSG, where he could better promote the World Cup in Qatar than back at Barcelona. These «secrets» are all pretty much out in the open. UEFA’s «Financial Fairplay» isn’t worth the paper it’s written on.

There’s more money in football today than ever before. Investors buy and sell clubs, piling up debt to offer stars wages of up to a million euros – per week. The liabilities of clubs such as FC Barcelona, Inter Milan or Chelsea are so high that a financial collapse might seem inevitable. Nevertheless, stars continue to be transferred back and forth. Much to the delight of the Association of Player Advisors. Players themselves have their own agenda, suddenly willing to brave a new league heading into the twilight of their careers (Lewandowski), feeling betrayed by their current club because they have to take a seat with the reserves (Ronaldo). Or they simply sit out high-paying contracts and go to the golf course on match days (Bale).

I cannot and do not want to support this any longer. Even if a player taps his chest after scoring a goal, or dares to kiss the crest of his current club – I just don’t care about these gestures any more. Most of these gentlemen have only their own career and profitability in mind.

Rehearsed celebrations are recycled in football simulations and presented to the next generation of football fanatics. In some of the most successful games ever, EA Sports’ FIFA series, gamers can spend a fortune on virtual trading cards – falling prey to methods reminiscent of psychological tricks from the gambling industry (article in German). In the analogue world, Panini packs the Qatar World Cup scrapbook with 670 empty sticker slots, more than ever before. In this new football world, fans have become the cash cow. A child’s allowance is up for grabs, parents’ household budgets get splashed on overpriced merchandise and pay TV.

I can’t do this any more. The football that FIFA and UEFA, sheikhs and oligarchs, players and agents have ruined is no longer the football I loved as a child and teenager. It’s a product. And that’s the worst insult I can think of.

Journalist since 1997. Stopovers in Franconia (or the Franken region), Lake Constance, Obwalden, Nidwalden and Zurich. Father since 2014. Expert in editorial organisation and motivation. Focus on sustainability, home office tools, beautiful things for the home, creative toys and sports equipment.

This is a subjective opinion of the editorial team. It doesn't necessarily reflect the position of the company.

Show all