Background information

Why do we buy things we don't need?

by Kevin Hofer

It's been twenty years since Brad Pitt forced his henchmen not to talk about Fight Club. We're doing just that right now. Or even better: we're still doing that. What makes David Fincher's dark satire as brilliant as it is timeless?

A modern city slicker who has everything he'll ever need. Apparently. Yet he suffers from insomnia. He deals with his problems in an underground martial arts club founded by himself, which develops into a national movement. Shortly followed by a terror cell wanting to overthrow the ruling system. That's «Fight Club». Viewers were and are amazed. Including user Retikulum.

He describes director David Fincher's work, based on the novel of the same name by satiric author Chuck Palahniuk, as a «real man's movie for an awesome evening, nothing for sensitive ladies». I disagree. At least partially. The film is violent. Very violent. But it doesn't glorify it. And it's definitely not anti-feminist.

So what's it really about? «Fight Club» is a dark satire. Essentially. Barely. But the film could just as well be a study on our base, violent and self-destructive drive. A feeling intensified by the anger that many of us adult viewers today felt damn well during our teenage years in 1999. This anger isn't just frightening – it's also fascinating.

Before you go on reading: yeah, I'll be spoiling relentlessly.

What fascinates me most about «Fight Club» is its viewpoint on a society that works and tortures its way to happiness. A world view that is broken down into its individual parts in the course of the movie. By anger. Until then, the film takes up provocative but never trivial themes such as fascism as a reaction to feminism, consumerism or overly civilised life.

We see this in the narrator, played by Edward Norton, who is called «Jack» in secondary literature and reviews. This comes from the novel. In it, the narrator repeatedly quotes passages from a magazine: «I am Jack's Medulla oblongata» or «I am Jack's wasted life» or «I am Jack's complete deficit of surprise». And so on.

Jack's a businessman. An insurance salesman who seems to own everything. Yet he can't find peace. Not even at night. As a narrator, he describes how lack of sleep is an expression of a restlessness stemming from his search for something resembling the meaning of life. Meaning: he collects Ikea furniture, which he uses to define himself. There you go. A society that works itself rich in order to be happy.

I feel kinda guilty. My apartment is stuffed to the brim with things I don't really need. Still, I bought them. Why? A question which my colleague Kevin has already dealt with.

In it Kevin mentions hedonism. Achieved by buying «goods that reinforce, weaken or maintain emotions in the short term. The positive emotions that are reinforced are joy or satisfaction, for instance.» This is totally true in Jack's case: he bases his self-worth on the things he owns. An expensive designer sofa, for example. Its material value not only symbolises prosperity, but also confirms good taste. Here’s the problem: the positive feeling when buying the sofa only lasts for a short time. To maintain it, he needs more. It's a vicious circle.

Am I just like Jack? Maybe. I hope not. Before I can get to grips with my own consumeristic behaviour, «Fight Club» already moves on to the next thing to brood over: feminism.

Jack seeks comfort in a support group for testicular cancer patients. Not that he has testicular cancer – he just pretends to – but being surrounded by the misery of others makes him feel sublime. These are his own words, by the way.

In one of these scenes Jack is in intimate embrace with Robert «Bob» Paulson (Meat Loaf). Bob had his testicles removed. The subsequent hormonal treatment made him grow female breasts and alienated him from his family, leaving Bob feeling lonely. «We are still men,» he breathes into Jack's ear in tears. If we believe Jack's portrayal, at least. After all, he's the narrator. Bob might not even be that weepy.

But the way us viewers get shown the scene, it's clear: in Jack's world, feminism is something real men must be afraid of. Removed testicles are a symbol of ravaged masculinity. And Marla Singer (Helena Bonham Carter) – a strong female character – who appears a few scenes later, promptly declares Jack as public enemy no. 1.

I'll admit. Jack tells us viewers something else. His hatred for Marla stems mainly from the fact that she only visits self-help groups to feel better about herself. Just like he does. She's the mirror he doesn't want to look into. Nevertheless: A self-assured woman of all people is much more masculine than he probably ever was, stirring up an almost irrational rage in him.

This can't be a coincidence.

Then Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt) appears. Tyler, is everything Jack ever wanted to be. Fearless. Confident in himself. Charismatic. He sells soap for 20 dollars a piece and lives in a completely dilapidated mansion with no cable TV and electricity that has to be switched off when it rains.

What us viewers only learn at the end: Tyler Durden is Jack's split personality. His inner rage. Tyler was created by Jack's mind simply so that Jack could do or think all he'd never do or dare to think. So unlike Jack, Tyler hardly has any possessions, which is exactly why he's free: «The things you own end up owning you,» Tyler says to Jack after about 30 minutes in.

Again, I have to think about hedonism. The way the film stages it – only without possessions are we truly free – we would probably all be hedonists. It is here that the movie uses social criticism the most. Personally, this goes way too far for me. But it's thought-provoking. That's good.

Then there's Jack's anti-feminist attitude, which he delegates to Tyler because he can't stand by it himself: «We're a generation of men raised by women,» he says, as the two talk about marriage. «I wonder if another woman is really the answer.»

In Fight Club, which Jack and his imaginary second personality founded, men from all social classes fight each other.

The Fight Club – as movie critic Owen Butler aptly describes it in Film Inquiry – is shown as a «toxic-masculinity-driven response to the powerless man from whom feminism must be driven out». Fight Club is also «the satisfaction of the need to be violent and nihilistic.» A need «caused by a consumer culture that is wise but also complacent».

For me, Butler's analysis is so accurate because it fits the following quote from Tyler Durden perfectly:

We've all been raised on television to believe that one day we'd all be millionaires, and movie gods, and rock stars. But we won't. And we're slowly learning that fact. And we're very, very pissed off.

From this perspective, director David Fincher paints the Fight Club's as a symbol of the wrath felt by a rebellious generation that believes itself lost. Lost in their meaninglessness. That's exactly what Jack fears when, at the beginning of the movie, he stands in front of the copying machine in his office with an empty gaze and quotes from Jean Baudrillard's «Simulacra and Simulation». By the way, a vital book in «The Matrix», which came out the same year as «Fight Club». I once wrote about this.

With insomnia, nothing's real. Everything's far away. Everything's a copy of a copy of a copy.

Media scholar Barry Vacker interprets Jack's statement as his anger at the loss of authenticity and individuality. As according to Vacker, consumer society does nothing other than hide its own meaninglessness in a flood of mass production. Symbolically, the copies of the copies Jack makes. With his Starbucks coffee close to hand.

If you ask me, Fight Club is nothing more than a tool with which members find their way out of this meaninglessness. For in the thrill – amidst adrenaline, blood and sweat – they find their way back to the authenticity they think they've lost in life. Here their anger at society – at people – manifests itself in the form of violence, beatings and brawls.

I spoke to Allan Guggenbühl, Swiss psychologist and leading expert on youth violence. According to him, the allure of «Fight Club» for many viewers lies in the fact that violence among men makes up a taboo form of masculinity that is usually hushed up in society. Be this hooligans in Swiss football stadiums or other kinds of youth violence. And talking about taboos is exciting.

But it's not the violence itself that fascinates audiences: According to Guggenbühl, the men in Fight Club create an alternate society where aggression is allowed and where violence does not divide but connects. The members punch and beat each other up, they even get injured, but nevertheless – or precisely because of that – they still belong together: a fascinating, if not recommended, paradox.

But this isn't where Fincher's study on anger ends.

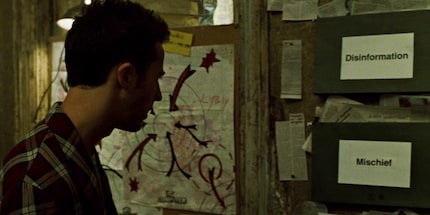

Project Mayhem is founded by Jack and his fictitious second self and aims to blow up the headquarters of every credit card company. This reset all public debt to «zero». An act of liberation from the materialistic consumer society controlled by a life of loans. A new beginning for everyone. A second chance.

Ironic.

After all, if it's Tyler who originally warns Jack of possession, who threatens to control him, then it's now his anger that takes over. Neither Jack nor Tyler can see that coming. But Project Mayhem is basically nothing more than an exaggerated version of the Fight Club, which is no longer enough to satisfy Jack's and especially Tyler's search for meaning. This goes so far that Tyler Durden's words boil down to complete barroom drab, becoming only prejudice and the spouting of meaningless phrases.

We’re the middle children of history, man. No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our Great War’s a spiritual war… our Great Depression is our lives.

However: Tyler hits a nerve that people respond to. Namely to follow the one that barks loudest against the prevailing, supposedly failed order. Historically, this is nothing new. During the Second World War, for example, millions of people followed a leader. Not least due to this, fascism is often mentioned when talking about «Fight Club». Roger Ebert, one of the most important film critics in the USA, even described the film as «openheartedly fascist».

Some parallels are actually present: the men who participate in the project submit to a strict order. At their head is a leader – in «Fight Club" this is Tyler Durden – who leads with complete power, is worshipped or even glorified. These are certainly some fascist traits. In an almost ritual way, the members renounce their name and thus their identity. They step into a faceless mass to become part of a larger order.

The members are liberators.

They're really modern-day terrorists. They are willing to sacrifice their own and the lives of others for a higher purpose. Because in death, they get back their name and identity. A ritual that finally gives their existence the meaning they never found before in life – just in death.

In death, a member of Project Mayhem has a name. His name is Robert Paulson.

Salvation.

So what's «Fight Club» about at the end? Is it really just a «real man's movie for an awesome evening» that glorifies violence and is anti-feminist?

I don't think so. It's a lot more than that. Personally, I believe it is most importantly a study on anger and its toxic, destructive effect on people. Toxic because Tyler Durden's thought spreads like a poison through Jack's brain and later even mutates into a national movement. Destructive, because it destroys entire existences and in the end even collapses skyscrapers.

Director Fincher also sets himself apart from Tyler. Only through staging. Because when Jack realizes that Tyler is the destructive extension of himself, us viewers feel as if we found our own inner Tyler Durden. Where we eagerly followed the plot up to that point and even secretly hoped that Tyler would be able to complete his plan, we do become aware of something thanks to Jack's insight: Tyler is evil. So is his anger.

Jack does remove his alter ego Tyler from his head by shooting himself in the cheek, but Project Mayhem is unstoppable. The skyscrapers of the credit card companies collapse in a fiery explosion. An appeal to viewers, a reminder to stop our own Tyler Durden – our anger – before it is too late for us as well.

I write about technology as if it were cinema, and about films as if they were real life. Between bits and blockbusters, I’m after stories that move people, not just generate clicks. And yes – sometimes I listen to film scores louder than I probably should.

This is a subjective opinion of the editorial team. It doesn't necessarily reflect the position of the company.

Show all